Germany stutters

The general election in Germany produced a sharp swing to the right. The two main parties of the centre-right and centre-left, the Christian Democrats/Social Union (CDU-CSU) and the Social Democrats (SPD) suffered significant losses in their share of the vote. The party of Chancellor Angela Merkel lost 8.5% pts from the 2013 election to finish with 33%; and the SPD lost 5.2% pts to finish with 20.5% – both achieving the lowest share of the vote since 1945. The share of the vote going to the two main parties, which were in a ‘grand coalition’, is hardly above 50% of those voting – and the voter turnout rose to 75% from 71% in 2013.

The big gainer was the anti-immigrant, ultra-nationalist, anti-muslim, Alternative for Germany (AfD) which polled 12.6%, compared with 4.7% in 2013 and entered the German parliament (Bundestag) for the first time. The other major gainer was the petty-bourgeois, neo-liberal Free Democrats (FDP) which polled 10.7% compared to 4.8% last time and re-entered the Bundestag. Die Linke (Left) party polled more or less the same as last time with 9.2% and so did the Greens with 8.9%. Indeed, the left (if you include the Greens in that) polled less than 40% of the total vote, even lower than in 2013.

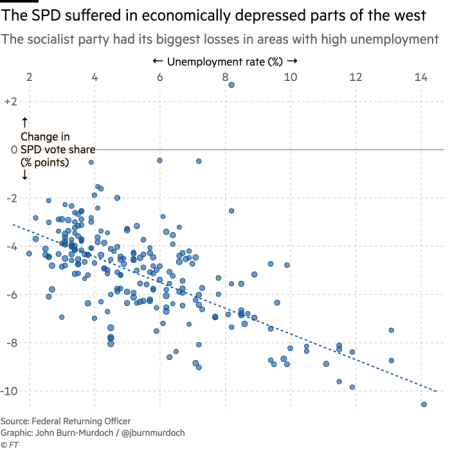

The SPD says that they will not enter a new grand coalition with the CDU, and that’s not surprising after the hammering they have taken in the election for being part of Merkel’s government. The SPD particularly lost support in higher unemployment areas of West Germany, revealing that the poorest sections of the working class do not see the SPD as fighting for them any longer.

The big gains by the AfD made it Germany’s third-largest party in the Bundestag. The phenomena of ‘populist’ right-wing nationalist parties that we have seen in France (National Front), the UK (UKIP), Italy (La Liga) and Greece (Golden Dawn) demonstrate the fragmentation of the political status quo in Europe in this Long Depression. Some (not all) of the poorest and least organised of the working class, along with small business and self-employed, have turned to nationalism for an answer. They think that the causes of their demise are immigrants, handouts to other EU countries and big business – in that order.

Germans are used to immigrants. Germany is the second most popular migration destination in the world, after the US. Over one out of five Germans has at least partial roots outside of the country, or about 18.6m. But the question of immigration became a huge issue in Germany because of the disaster of the Middle East and the massive and fast influx of refugees, around 2m in the last two years into Germany. Most of these refugees were placed in the poorest parts of east Germany, already under the pressure of poorer housing, education and social services.

It is an economic issue because of the previous policies of the SPD and CDU in introducing so-called labour ‘reforms’ that created a whole layer of part-time temporary employees for German business on very low wages. This is what Marx called a ‘reserve army of labour’. This kept labour costs down for German industry and laid the basis for the sharp rise in the profitability of German capital from the early 2000s up to the global financial crash.

About one quarter of the German workforce now receive a “low income” wage, using a common definition of one that is less than two-thirds of the median, which is a higher proportion than all 17 European countries, except Lithuania. A recent Institute for Employment Research (IAB) study found wage inequality in Germany has increased since the 1990s, particularly at the bottom end of the income spectrum. The number of temporary workers in Germany has almost trebled over the past 10 years to about 822,000, according to the Federal Employment Agency.

So the reduced share of unemployed in the German workforce was achieved at the expense of the real incomes of those in work. Fear of low benefits if you became unemployed, along with the threat of moving businesses abroad into the rest of the Eurozone or Eastern Europe, combined to force German workers to accept very low wage increases while German capitalists reaped big profit expansion. German real wages fell during the Eurozone era and are now below the level of 1999, while German real GDP per capita has risen nearly 30%.

This cheap labour, concentrated in the eastern part was in direct competition with the huge numbers of refugees arriving in the last two years. The irony, as always, is that the AfD vote improved mainly in areas in Eastern Germany where immigration was relatively low – you see, it is the fear rather than the reality that drives such prejudice and reaction.

The other irony is that the co-leader of the AfD is no poor populist of the people, but instead Alice Weidel is a former economist at Goldman Sachs and financial consultant – shades of UKIP leader Nigel Farage, who is a stockbroker. These representatives of capital have no connection with their rank and file voters but attempt to rise to power on prejudice and mendacity.

What the result shows is that even German capitalism, the most successful advanced capitalist economy in the world, cannot escape the divisive forces of the Long Depression. Germany is the EU’s most populous state and its economic powerhouse, accounting for over 20% of the bloc’s GDP. Germany has preserved its manufacturing capacity much better than other advanced economies have. Manufacturing still accounts for 23% of the German economy, compared to 12% in the United States and 10% in the United Kingdom. And manufacturing employs 19% of the German workforce, as opposed to 10% in the US and 9% in the UK.

Even so, economic growth since the last general election has been little better than the UK and the US, but that was better than during the euro debt crisis just before the last election in 2013, when there was a short recession.

What has changed economically since the last election in 2013 is yet another fall in the average real wage growth for Germans particularly in this last year before the vote. The election took place just as many Germans were starting to feel the pinch for the first time since the last election.

The profitability of German capital has risen steadily, on the whole, since the end of the global profitability crisis of the 1970s, which affected all the major economies. The real take-off in German profitability began with the formation of the Eurozone in 1999, generating two-thirds of all the rise from the early 1980s to 2007. German capitalism benefited hugely from expanding into the Eurozone with goods exports and capital investment until the Great Recession hit in 2008, while other Euro partners lost ground. Also, the Hartz labour reforms that opened up a bigger gap between productivity growth and wages in Germany than anywhere else in Europe.

But the fall in profitability during the Great Recession was considerable and profitability since has remained below pre-crisis levels. That tells us that Germany will struggle to grow much more than it has done over the last few years.

So what happens now? The formation of a new German government will probably take months to work out. As the SPD currently refuses to join a new coalition, Mrs Merkel will have to try to form what is called a ‘Jamaica’ coalition (based on the black, yellow and green party colours of the CDU, the FDP and the Greens). If that is formed, and it remains an ‘if’, it is likely to be much more unstable than the last government. The FDP and the CDU want to carry out even more neo-liberal measures, including large cuts in corporate tax for big business. And the FDP is opposed to any further integration in Europe or fiscal transfers to the weaker euro area states. The Greens want a total end to nuclear power and other environmental measures unacceptable to the FDP.

This election shows that, even in Germany, there is growing disillusionment with the ‘success’ of capitalism that has given just a few crumbs for the working class off the table of bounty for German business – less than one in four adult Germans voted for the main party of capital. So far, that disillusionment has been expressed in a partial switch to nationalism. If there is a new global recession in the next four years, the so-called ‘stability’ of German politics will crumble further.

No comments:

Post a Comment